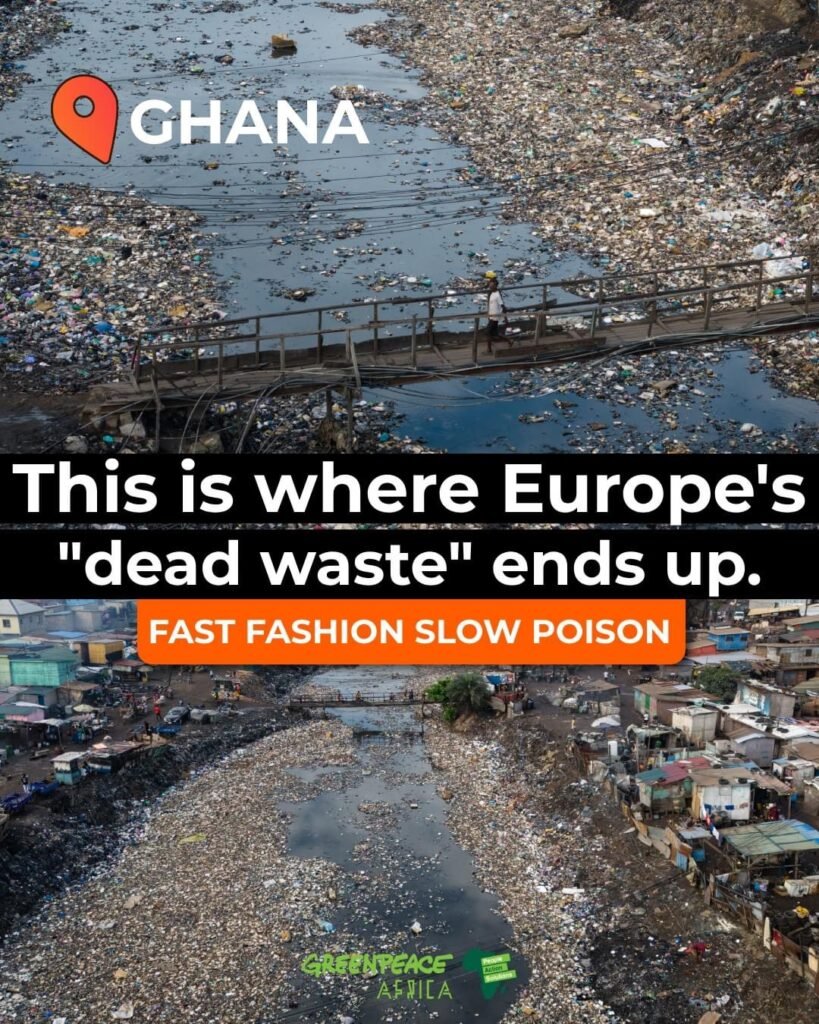

A shocking new report by Greenpeace Africa, in collaboration with Greenpeace Germany, has exposed the devastating environmental and public health impacts caused by the relentless influx of fast fashion waste into Ghana. The report, “Fast Fashion Slow Poison: The Toxic Textile Crisis in Ghana,” reveals how the nation’s informal waste disposal sites are being overwhelmed by millions of unsellable clothing items from the Global North each week. The report brings into sharp focus the environmental degradation, pollution, and social consequences resulting from this unchecked practice.

Every week, approximately 15 million pieces of unwanted fast fashion apparel arrive in Ghana, the majority of which end up as waste. This surplus of second-hand clothing has not only created significant challenges for waste management systems but has also adversely affected local communities who rely on the second-hand clothing trade for their livelihoods.

Greenpeace’s research has uncovered serious health hazards associated with this waste. Air samples collected near informal dumpsites revealed the presence of carcinogenic substances such as benzene, which pose grave risks to the health of nearby residents. Moreover, almost 90% of the discarded clothing is made of synthetic fibers, which contribute to microplastic pollution in Ghana’s soil and water bodies. One of the more visible signs of environmental damage is the formation of “plastic beaches” along the Ghanaian coast, a disturbing illustration of how textile waste is smothering natural habitats.

Beyond these environmental concerns, the report also highlights a growing socio-economic problem that is severely impacting Ghana’s second-hand clothing traders—many of whom are struggling to survive in an industry that is increasingly flooded with unwearable, low-quality garments.

The Traders’ Struggles: “We Run at a Loss”

For second-hand clothing traders, the fast fashion waste crisis is more than just an environmental issue—it’s a direct threat to their livelihoods. Elizabeth Nartey, a long-time trader in Accra, paints a bleak picture of the challenges traders now face.

“Some years ago, selling second-hand clothes was a good business,” Nartey said. “However, for some years now, when the clothes arrive, about 60% are waste—clothes that no one can even wear. So we always run at a loss whenever we buy bales.”

Nartey’s experience reflects a larger issue faced by traders across the country. Once a viable source of income, second-hand clothing markets are now dominated by unusable waste, leaving traders like her with stock they cannot sell. The financial strain is compounded by the fact that traders still have to pay for these “bales,” many of which are filled with clothing that is either too damaged or too worn out to be sold.

“It’s not just a loss for us financially,” Nartey continues, “the waste found in the bales also adds to the already huge waste management issues in the country. We’re pleading with the middlemen and the government to filter the second-hand clothes before they send them to Ghana. If they don’t, we traders will continue to suffer, and the environment will continue to bear the brunt.”

Traders like Nartey are not just losing income, they are witnessing firsthand how this waste problem contributes to the country’s broader waste management challenges. In a country where solid waste disposal is already a major issue, the addition of millions of unsellable garments each week is exacerbating an already strained system.

Fast Fashion’s Toxic Legacy

The Greenpeace report paints a grim picture of the future if no immediate action is taken. The rise of fast fashion in the Global North has led to an explosion of cheap, disposable clothing being manufactured and sold at breakneck speed. When these items fall out of favor with consumers, they are often shipped to countries like Ghana under the guise of “second-hand donations.”

However, instead of contributing to a circular economy or benefitting local markets, the vast majority of these garments are unsellable. Greenpeace Africa has urged governments in both the Global North and South to implement stricter regulations on the export and import of second-hand clothing. According to the report, fast fashion brands, many of which have pledged commitments to sustainability, must take responsibility for the end-life of their products.

Ferdinand Omondi, Greenpeace Africa’s Communication and Story Manager, has called for a global response to the textile waste crisis. “We cannot allow Ghana and other African nations to continue being used as dumping grounds for the world’s fast fashion waste. This is not just an environmental crisis, but a human rights issue. Local communities are suffering—both economically and health-wise—because of irresponsible consumption patterns in the Global North.”

Greenpeace’s findings have shown that informal waste dumpsites across Ghana, particularly in urban areas such as Accra, are saturated with unsellable clothing, many of which release harmful chemicals when burned. The report identified severe air pollution in these areas, with traces of benzene and other toxic chemicals found in the air, posing serious risks to nearby residents. In addition, the influx of synthetic clothing contributes significantly to the rising levels of microplastics in Ghana’s water bodies, further polluting local ecosystems.

A Call to Action: Accountability for Fast Fashion Giants

The “Fast Fashion Slow Poison” report concludes with a call to action for fast fashion brands, governments, and international bodies to take responsibility for the escalating crisis.